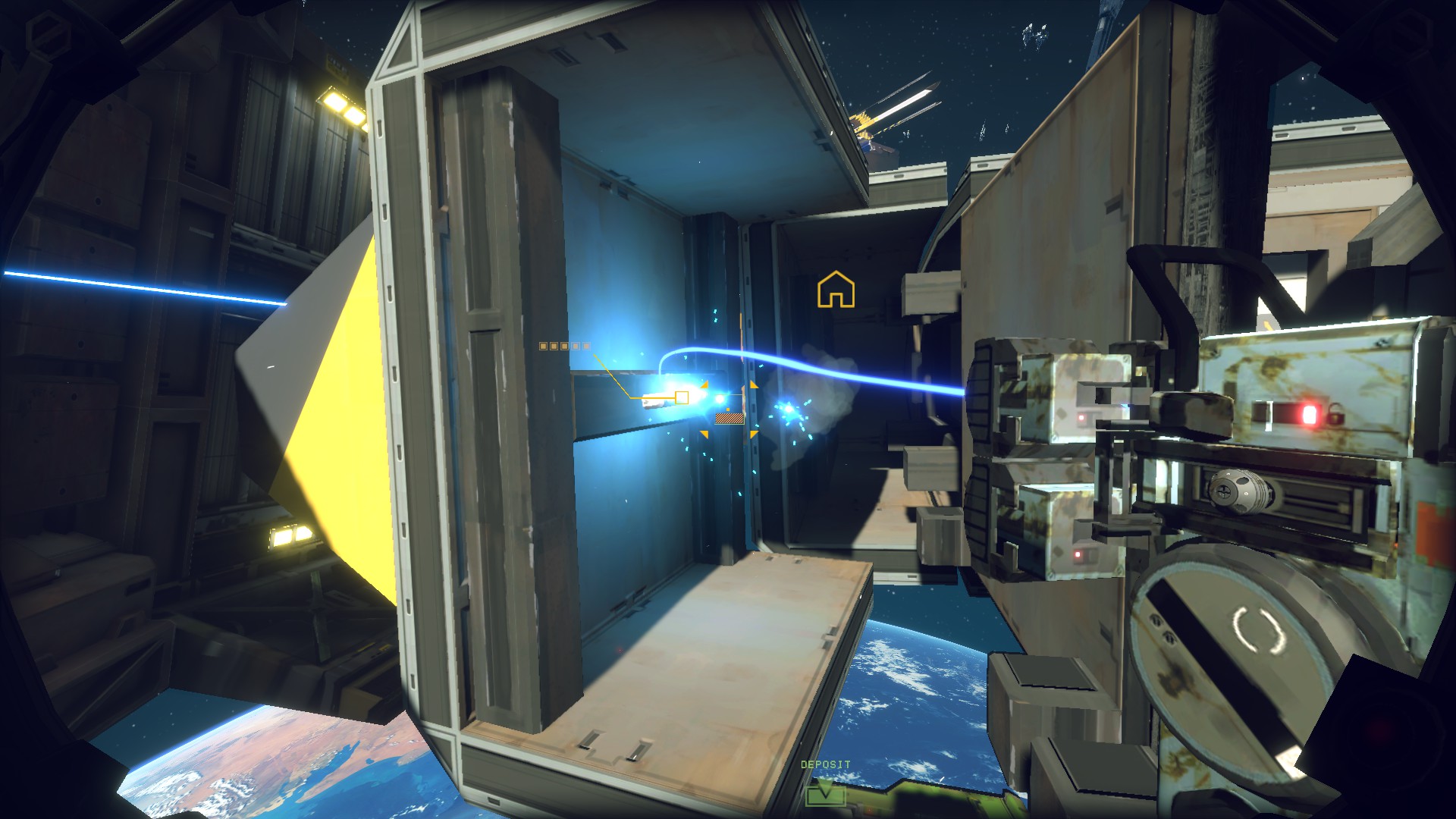

Despite being an estimate year from release, Hardspace Colon Shipbreaker already gets a lot of things right. But my favourite thing about it is one I didn’t even expect to feel so good: peeling the armour off a ship. The basic idea is near self-explanatory. You’re a salvage worker taking apart disused ships in a drydock, leisurely jetpacking around in zero gravity, climbing (or cutting) inside them before cutting them down from within. You need to extract the complex components like engines, computers, and even furniture, and slice the metallic frames into manageable chunks for the furnace. All while keeping the ship from exploding, the fuel and coolant from leaking, and yourself from being fatally electrocuted. All of this is satisfying. But the part that’s brought me such unexpected joy all week is the moment when you take off the armour plates. Your main grabby magnetic hook thing can tug lights off the wall and computers from their housing. It can push aluminium plates around, or propel you off a large enough mass in an emergency. It’s sort a cross between the gravity gun and a slightly unreliable telekinetic arm. Its secondary function shoots out tethers, which link any two items or surfaces, and produce a force that gradually pulls them together, based on a robust Newtonian physics model. So if you attach a support beam to a packet of crisps, don’t expect the beam to go anywhere. The main use of them is for dragging something to the furnaces. Just point at the loose item you want sent, point the other end of the tether directly into the fire and - blap! - off it goes. I don’t use the tethers much. Even though the tutorial man repeatedly emphasises how much you should use them, I move most of my salvage out of the ship manually. Tethers aren’t free, you know. But the exception to that is the armour. And here’s why.

It’s the best feeling. Aside from those panels being very valuable quite literally en masse (you’re paid for raw materials by the kilogram), the sheer delight of seeing such massive bits of a ship slip away hits me somewhere primal. Standard panels (I’d estimate 2 x 2 metres) like the basic floor and roof will immediately drift when released from the tight shell of the ship. But with the bigger, less regular pieces of armour, there’s sometimes a tiniest give when you decouple them. That’s weirdly satisfying. And sometimes there’s none at all, and you don’t know that it’s disconnected until you confidently space-stride forward and spend a tether to yank it out like those maniacs in old timey comics dealing with an aching tooth by tying it to a door handle and slamming it shut (side note: what the hell was that all about?). Then you get the satisfaction of watching it peel and curl away multiplied by the feeling of having expert knowledge. If you just try to yank the armour, see, it will do nothing. It’s still fused with the ship. First you have to go inside, and cut the correct joints affixing it to the inner frame. That’s a huge part of why Shipbreaker is so rewarding. You don’t get better by training your reflexes, increasing numbers, or memorising statistics and maps. Sure, you become familiar with typical layouts, but the real skill in the game is one of deduction. A little experience taking apart simple models gives you the base knowledge you need to deal with any ship in the game so far. On my first shift with a Gecko, the biggest ship (though I imagine it will be a medium at most by the time of a 1.0 release) yet, I spent the whole time just exploring and analysing its layout. The only cut I made was a small hole to climb into the engineering section. Despite that ship’s complex pipes, awkward skeletal structure, and its volatile reactor being about 8 times the size and far more difficult to extract than the miniature ones I’d dealt with before, I was able to systematically take it all apart with only one minor accident. Knowing, even when there’s no visible tell, that you’ve made the right incisions to pull away that section now? That’s special. And heaving away its massive armour chunks? Heaven.