I’m not sure if it was a consequence of recent build changes, advice supplied by the game’s designer, or experience gained from my numerous failures, but early this week Terra Incognito – Antarctica 1911 surreptitiously metamorphosed from “maddening” to “moreish”. Levels in my preview build that had felt impossible began to feel possible. I found that I was no longer so busy frantically issuing orders and fretting about frostbitten personnel, that I couldn’t plan properly or glance about occasionally and savour the atmosphere.

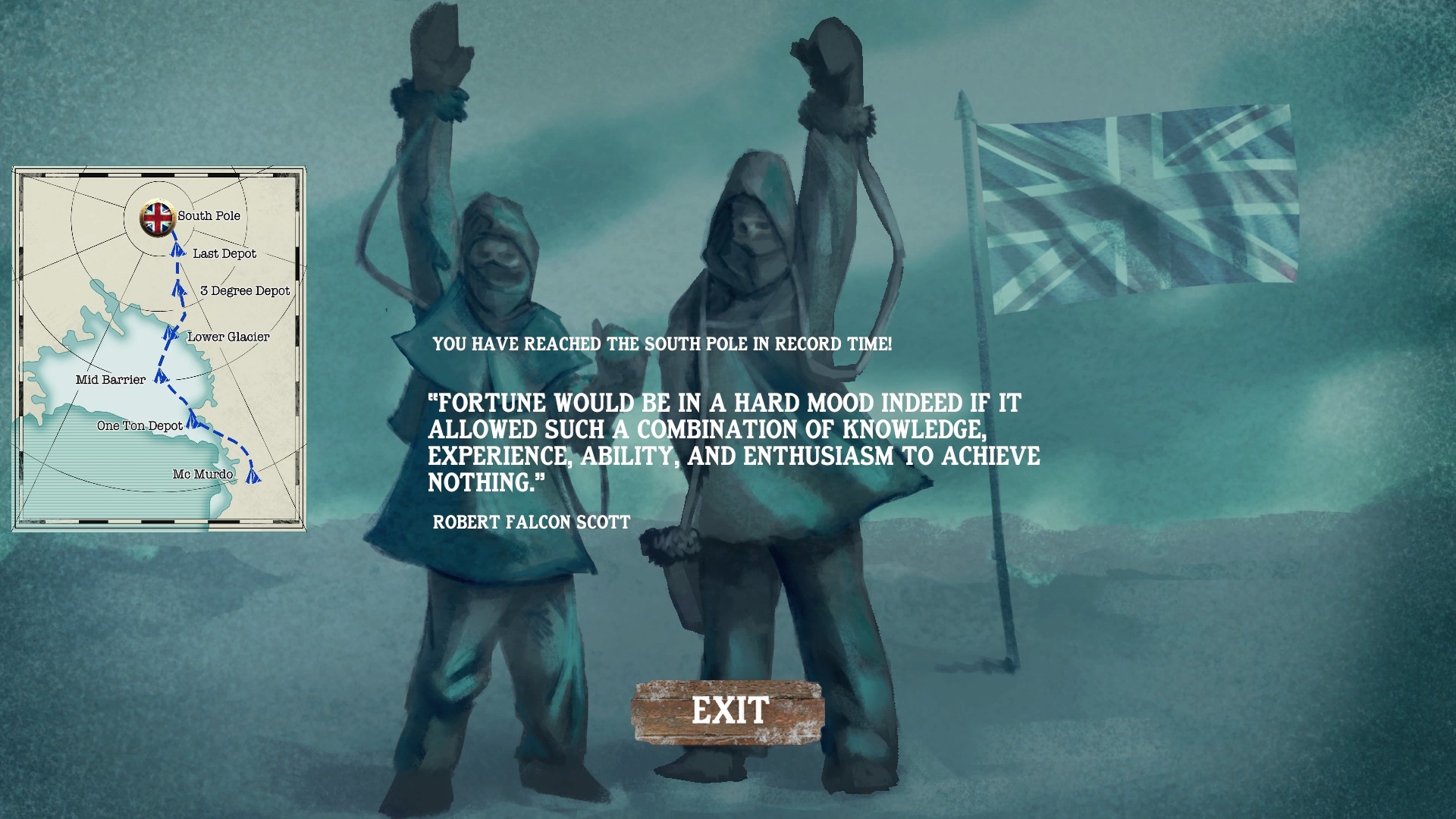

Make no mistake, reaching the South Pole in Johan Nagel’s imminent (March 19) and characteristically idiosyncratic Scott-em-up remains far from easy, but once you’ve grasped some basic play principles like… It’s wise to use one of your two explorers as a lightly-loaded scout/camp establisher, and the other as a shuttling supply mule. …the game blossoms.

Turning a long, weary trudge across a featureless monochrome wilderness into an entertaining tactical diversion is no mean feat. Nagel manages it by stylising then entangling many of the factors that warmed the balaclavas of real South Pole strivers like Scott, Amundsen, and Shackleton.

At its core Terra Incognito is a game about managing logistics. Explorers are slowed by heavily loaded sledges and perish if they spend too long away from camp stoves and rations. It’s up to you to ensure that their burdens are practical and the protective tents they pitch, sensibly placed and properly provisioned.

Meteorology and terrain both complicate the action deliciously. Because weather conditions determine how quickly explorers lose vitality, it’s not uncommon to find yourself debating whether to brave blizzards or sit them out (a three-day forecast is provided). A slog through horrendous conditions isn’t just physically demanding, it’s disorienting. Severely reduced visibility together with a mini-map rendered close to useless by frost and ice, can lead to awfully plausible spatial confusion.

Randomly-generated landscapes that must be revealed with a telescope and traversed with the aid of ladders, add another interesting element to decision-making. Would I have preferred it if the troublesome terrain has consisted of crevasses and rubbled ice, rather than stretches of seawater? Yes, for the same reason I wish there was a “no polar bears” checkbox in the options menu.

But turning a blind eye to a few anatopisms and graphics shortcomings shouldn’t be hard given the come-hither price point. For a five-dollar plaything, Terra Incognito generates an awful lot of fresh, interesting, unscripted dilemmas, plus, when you do finally reach your goal, the kind of furnace blast of satisfaction that games rarely produce.

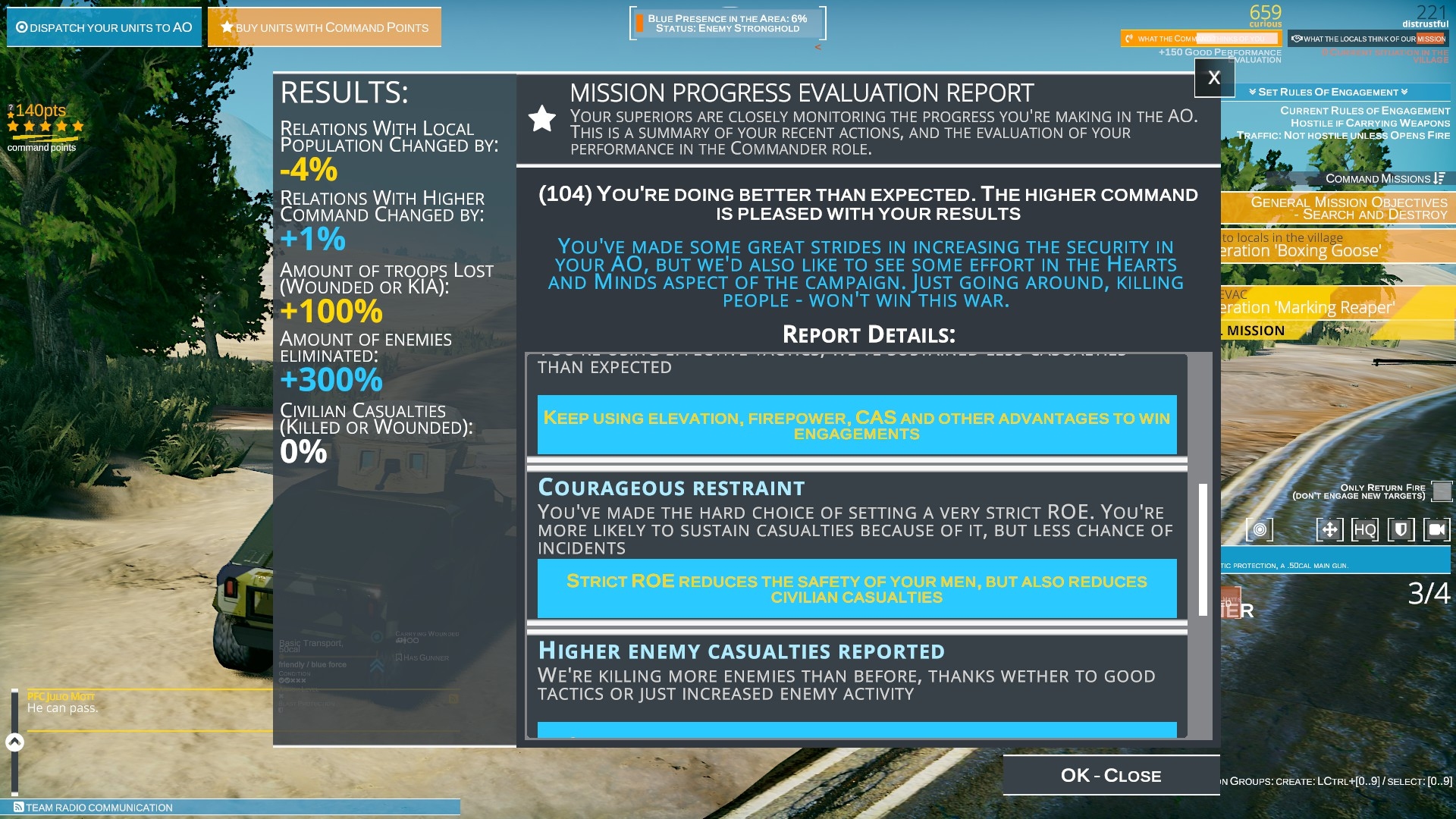

I wish I could be as complimentary about Invasion Machine. An Early Access RTS with lots, thematically and philosophically speaking, in common with Afghanistan ‘11, Pixel Machine’s debut is disappointingly light on content at the moment.

Purchasers have a grand total of one play mode to choose from - sandbox - and that always uses the same two-village map. More damagingly, saving is yet to be implemented, the AI is patchy, and an unhelpful GUI (there’s no mini-map or team monitor, and the unit icons and GUI texts are so subtle they’re almost camouflaged) makes simple tasks like identifying and selecting friendly forces, and moving around the battlefield quickly, far trickier than they need to be.

I’d have uninstalled after half an hour of eye-strain and nose wrinkling if it wasn’t for the clutch of decidedly New Wave features that give IM rare character.

For starters this isn’t one of those of RTSs where you slap down a base and begin churning out cannon fodder. Every soldier has a name, a specialism, and a stress stat (frazzled fighters must be sent back to an abstract HQ to regain equilibrium). Order wheels include novel instructions like “inspect passing vehicles”, “check for survivors”, and “search house for contraband”.

Working from a relatively safe “Green Zone” on the edge of the map you endeavour to purge the district of troublesome insurgents while keeping local civvies on side, and friendly losses to a minimum.

The hearts and minds battle is won through social projects like the refurbished petrol station pictured above, aid deliveries, village patrols, law enforcement, and random acts of kindness (in my last game one of my medics saved the life of wounded civvy brought to a vehicle checkpoint). Reducing trigger-happiness through a nifty Rules of Engagement panel also helps.

Triumphing in the traditional bullets and bombs contest involves eliminating, with a range of purchasable AFVs, infantrymen, and off-map assets, the improbably cocksure “guerrillas” who roam the map organising ambushes, planting IEDs, and intimidating settlements.

Firefights tend to have two phases. When the AK-47s and M4s cease their prattling, the race is on to stabilise bleeding friendlies (and enemies too, if you’re feeling merciful) and get them back to HQ ideally in an ambulance (Presumably CASEVAC by helicopter will eventually be an option). Casualties, so often swept under the carpet or simplified to the point of invisibility in wargames, disrupt and distract as they should in this one.

An RTS with a conscience and a fresh angle, Invasion Machine is barely demo-sized at present - slightly worrying considering coding began in 2015. The lone Polish developer will have to pick up the pace in order to finish by Q2 2021. I intend to return once the campaign is in place, the guerrillas have been supplied with RPGs and mortars, and that ghastly GUI has been consigned to the dustbin.

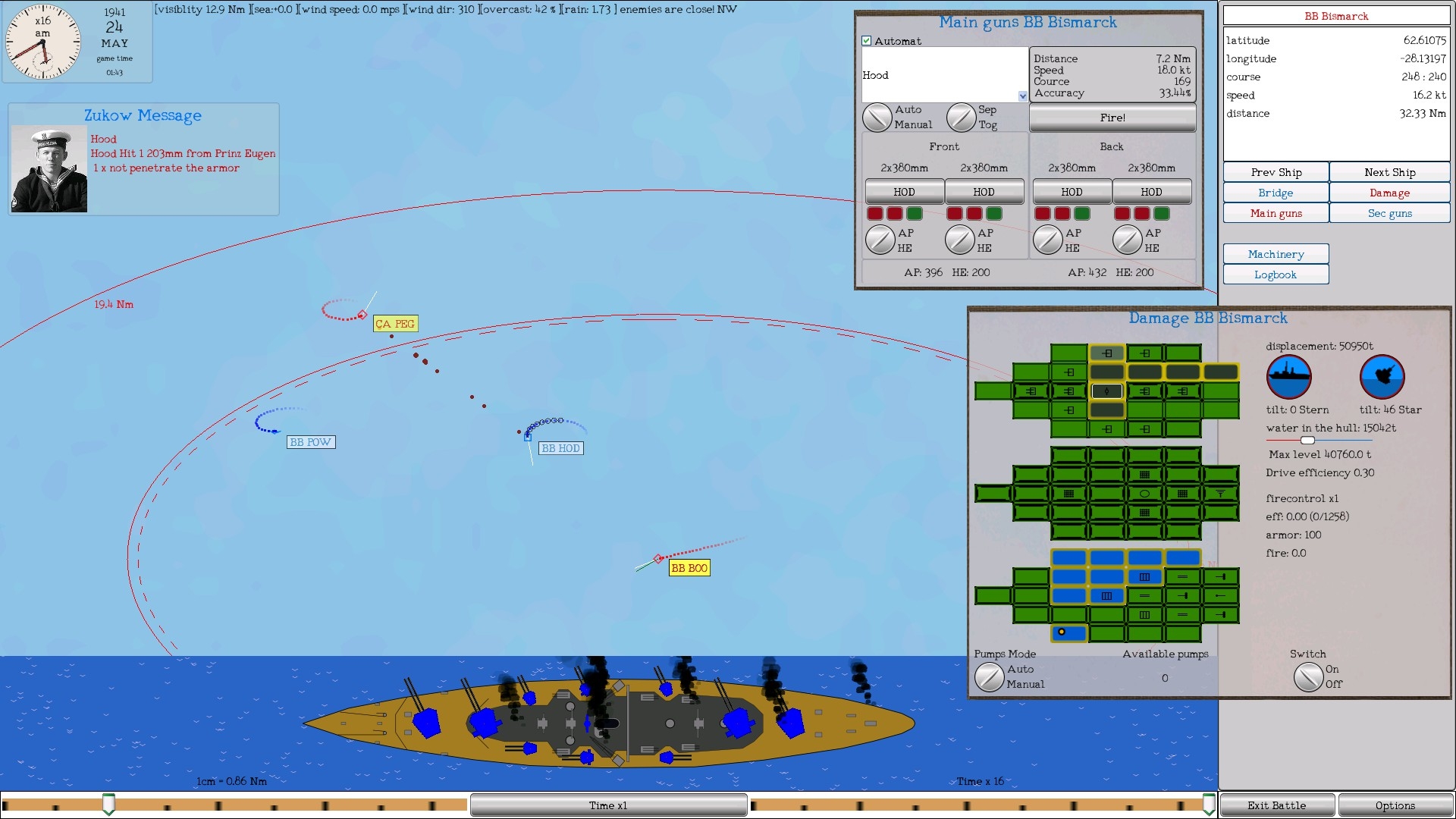

Naval Battles Simulator also has interface issues. In the tactical portion of Anarchy97’s dual-layer WW2 turnless Early Access wargame, you’re expected to devise your own screen layout with a flotilla of movable windows. It’s an old-fashioned approach that has lost currency for good reason.

Happily, this quirk, inadequate documentation, absent aircraft and minor AI issues seem to be the worst of this attractively priced (£12) offering’s problems.

Because it’s a relatively simple affair and a historical episode I know well, most of my tactical tests thus far have been conducted using the Battle of the Denmark Strait scenario (one of sixteen standalone scraps). While outcomes aren’t perhaps as colourful as they could be (I’ve yet to witness an incidental turret malfunction or a catastrophic Hood-style explosion, for instance) and badly mauled ships in patently hopeless situations are too reluctant to run, the post-aggro battle tracks and damage statistics never look ludicrous. As you’d expect, although the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen usually prevail, the elderly Hood, and green, barely finished Prince of Wales seldom die cheaply, assuming they close aggressively and coordinate fire.

Unless I’ve missed a trick, right now there’s no easy way to assess the condition of a target – no equivalent to the top-down ship representations or three-storey cellular damage diagrams provided for player vessels. That’s something I hope to see addressed in the “six to ten months” NBS is Early Accessible.

Without a manual or decent tutorial the campaign engine is a tad intimidating at present. As a result I’ve only used it as a skirmish generator. Tick the “CPU vs CPU” checkbox in the options, and hasten the chronometer, and an accelerated, completely dynamic Battle of the Atlantic/Mediterranean begins unfolding on the handsome weather-influenced chart in front of you. Whenever a clash occurs, the computer asks if you’d like to participate.

In between engagements, even if you’re not personally organising taskforce and convoy movements, or designing your own warships, there are distractions. Anarchy97 tell the story of the wider war with earcatching snippets of period audio and excerpts from the letters of a serving sailor, who, I assume, could perish at any point, if Fate is unkind.

Wargames set on flat blue battlefields rarely grip me as tightly as wargames set on lumpy green ones (the tactical possibilities always seem more limited). While Naval Battles Simulator doesn’t buck this trend, I like what I’ve seen so far, and suspect the campaign engine, once fully explained, could prove quite the rip tide.

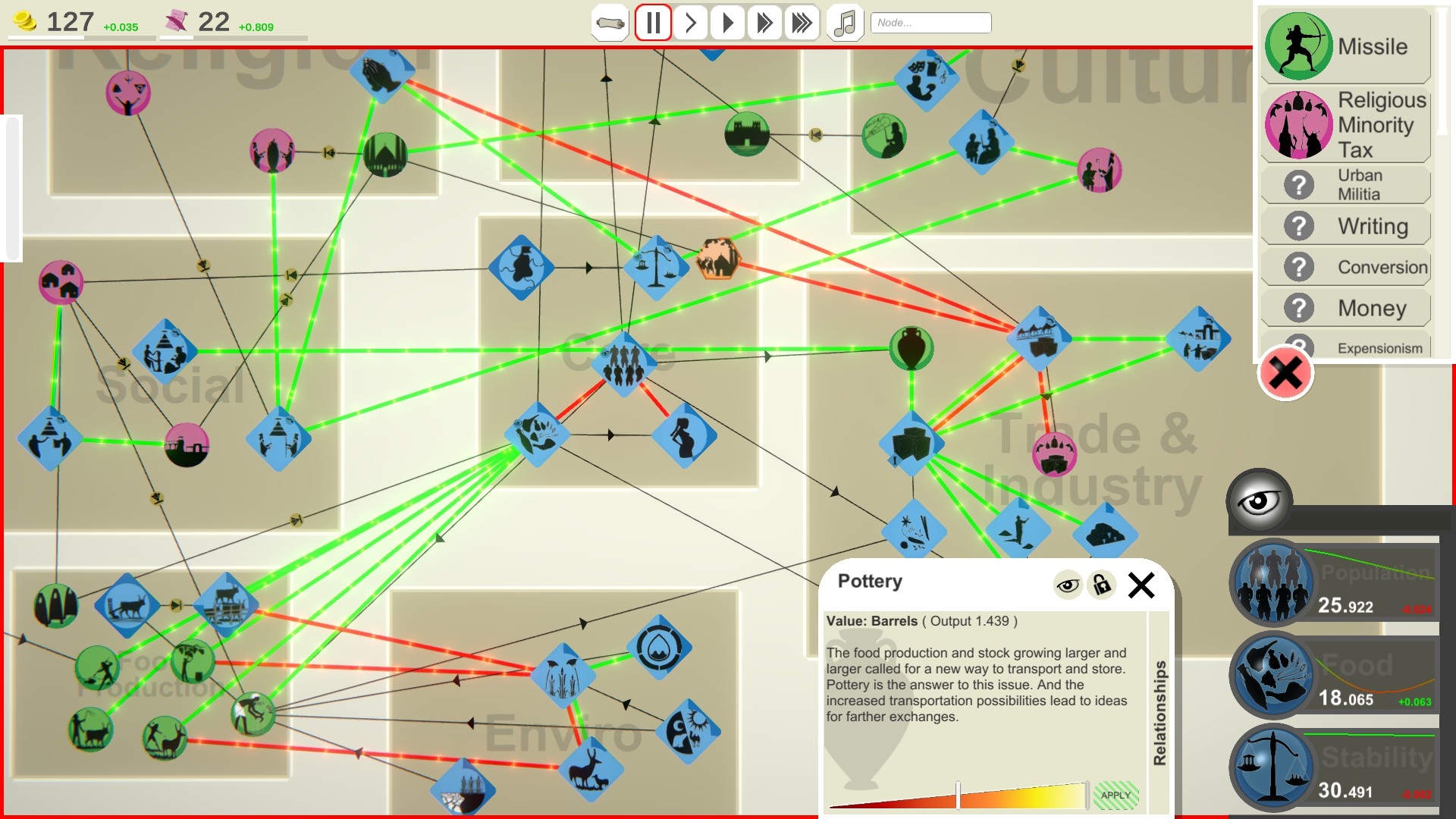

The game I’ve played most this week has the brain of a history professor and the physique of a marathon runner. The improbably compelling Orbi Universo (£11) is basically freeze-dried, turn-stripped Civ. Civ without bourgeois luxuries like maps and movable warriors.

Actually you can move soldiery about in Orbi, but the movements have no tactical consequences. You rearrange for the same reason a surgeon rearranges her instruments or a cockpit designer shifts gauges on a CAD model.

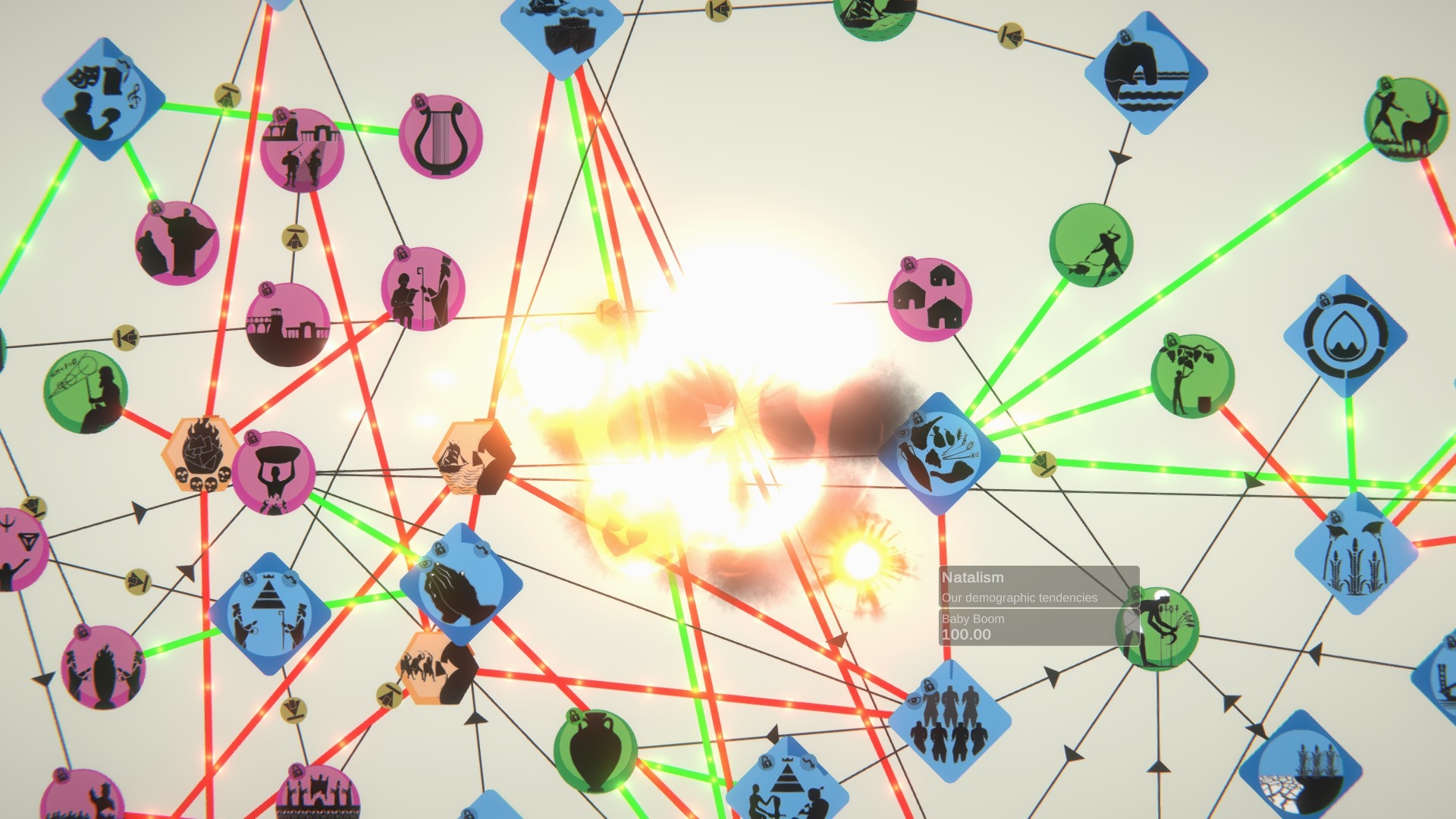

Not unlike Positech’s Democracy series in appearance and approach, Orbi is a little opaque thanks to a partially hidden tech tree and the odd bit of idiosyncratic translation (I believe the devs are French), but the experimentation you’re forced into as a result is so absorbing that I find I don’t resent the reserve.

Every game starts with the choosing of a homeland. By placing a dot on a globe and fiddling with various sliders (difficulty-rated history-inspired presets are also available) the cradle of any civ you care to mention can be approximated.

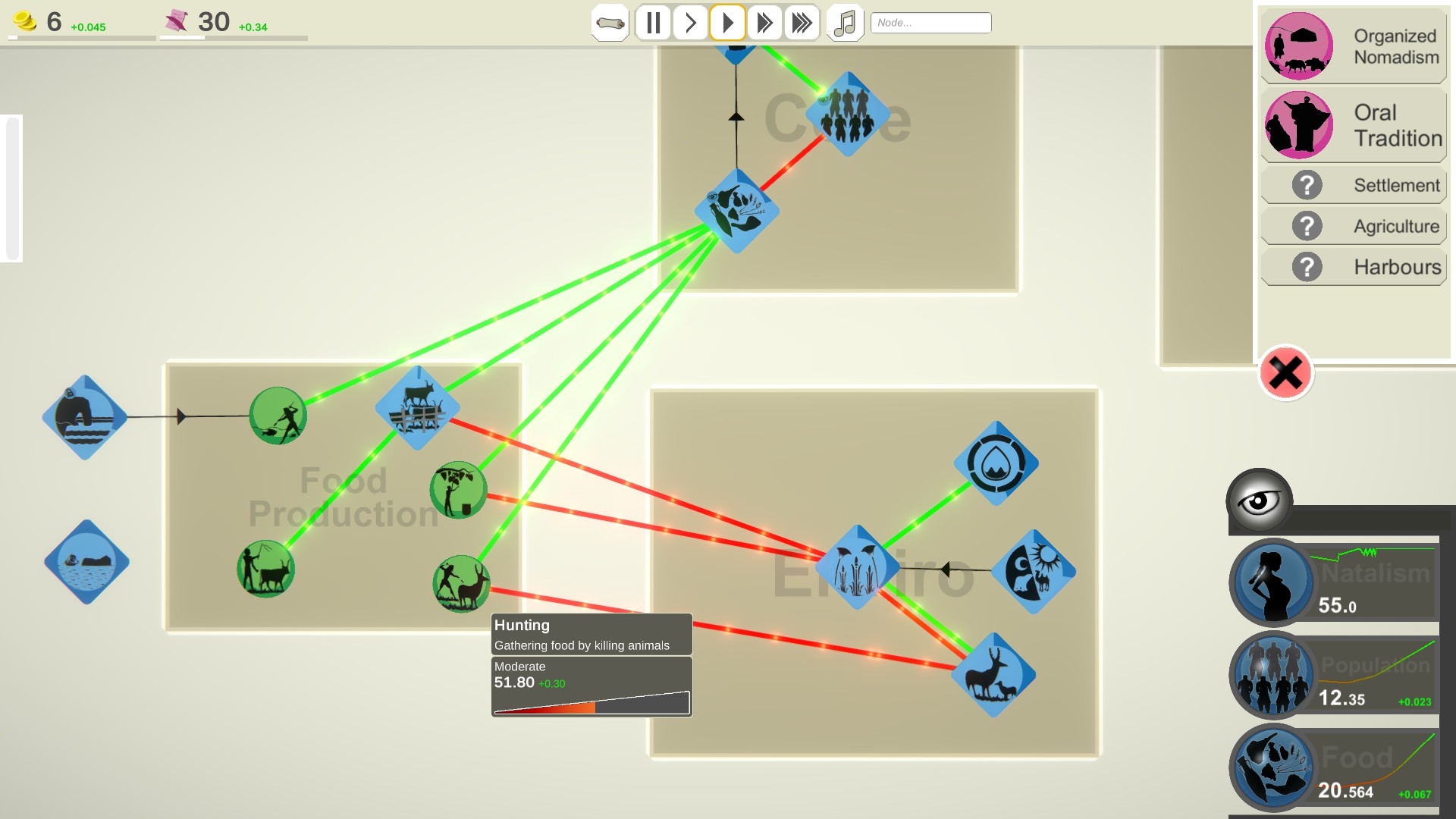

Then you’re presented with a play area empty except for eight diamond-shaped ’nodes’ representing core elements like food, population, birth-rate and the state of the local environment, and the fun begins.

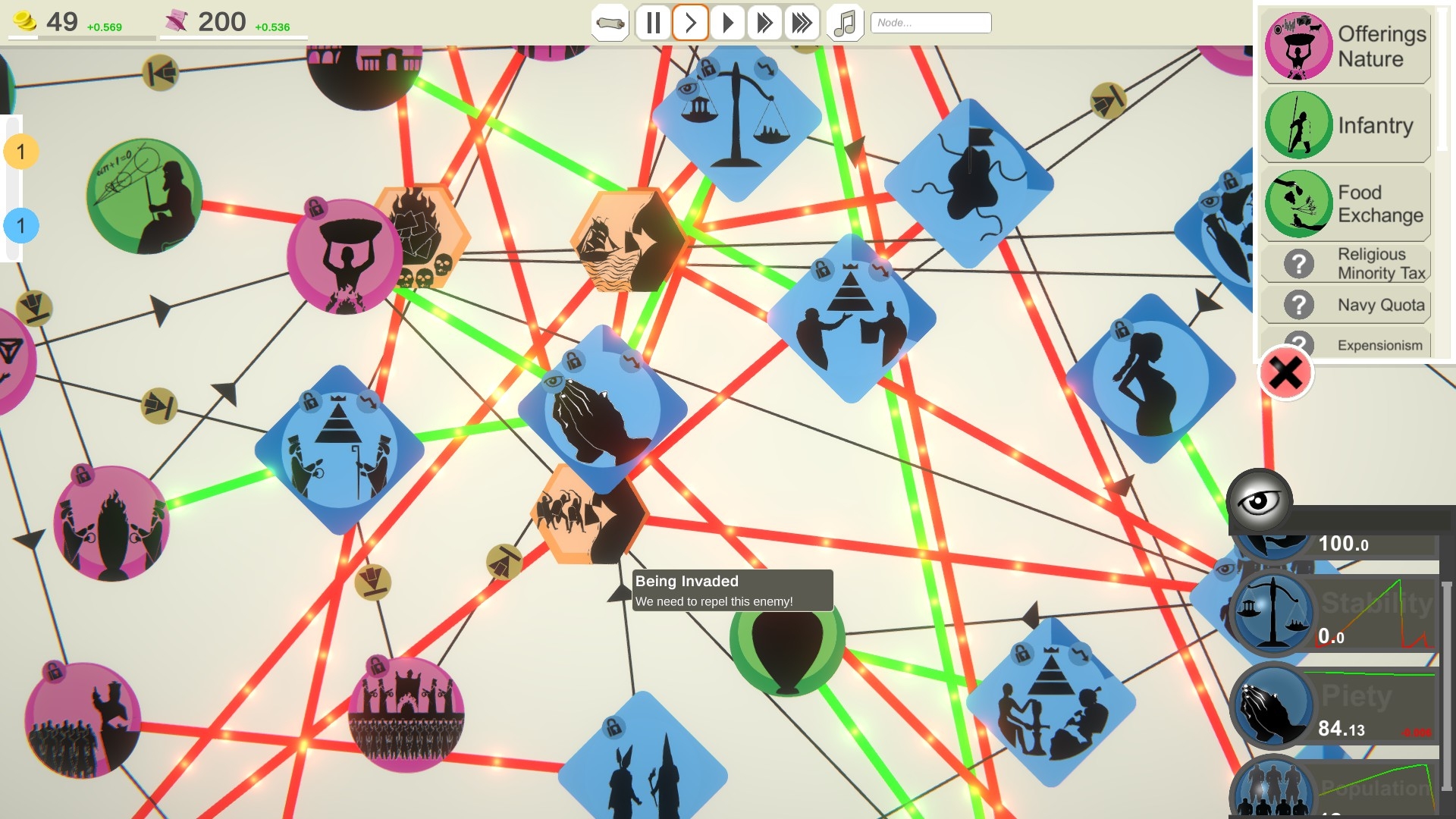

During the chariot-swift hours that follow, the rearrangeable web of interconnected variables steadily grows in size and complexity, as you purchase, with a constantly replenishing ‘political power’ resource, new adjustable governmental ’levers’ and choose new developmental paths. Food, stability, and wealth are major preoccupations. Allow any of these variables to flatline and the pale apricot-coloured hexagons that represent crises like famines and uprisings soon start sprouting.

Even if your economic and social actions are deft and timely, your civ can be cut off in its prime by invasion. Fail to heed the neighbour bellicosity node, to invest in diplomacy or make appropriate martial preparations, and the results can be catastrophic. Surprisingly, given the utilitarian presentation, Orbi tells very colourful stories. Wars, natural disasters, famines, religious schisms… it’s all here.

Seven hours in and I’ve yet to nurse any civ beyond the Iron Age (progression into the Dark and, confusingly titled, Feudal Age is theoretically possible) or employ the majority of the game’s 190+ node types. I’ve experienced fleeting moments of societal spasm when the game’s subcutaneous algorithms seem to glitch, but nothing disruptive or obvious enough to warrant the term “bug”. Periodically during play sessions, I get beguiling glimpses of wargames built in OU’s image. That COIN game about The Troubles I discussed a few months back – it’s easy to picture it in mapless, nodal form.

Will you enjoy Orbi Universo as much as I do? If you’re partial to a bit of history and enjoy tinkering with things mechanical, my guess would be “yes”.

To the foxer