That past involves violent witch trials of a Salem-y nature, and more recent economic devastation. Your control switches between all of the characters, and through a mix of split-second decisions, exploration of creepy ruins, and quick time events as you run from monsters, the group will either die horrible deaths or survive until morning for the revelatory plot twist. And while Little Hope is better than last year’s Man Of Medan, I wouldn’t say it reaches the heights of being actually good.

Will Poulter’s level-headed but perpetually confused Andrew is joined on his night of misadventure by Taylor, a young woman still given to bouts of adolescent behaviour; Daniel, her secret boyfriend and token arrogant jock type; Angela, the mature student who is defensive and kind of a massive bitch; and John the professor, pompous and self-appointed responsible leader who throws his charges in the path of danger every chance he gets. The intriguing hook is that each of these characters has a doppelganger in the 17th century witch killing community, and in a family who burned to death in the 70s. Early on, Little Hope does pretty well at showing not telling. The tension ramps up slowly, as the team make their way into the town proper, and creepy tropes start coming into play. There is fog that prevents them leaving town, a dude drinking alone in a run-down bar who gives cryptic responses to everything you say, and a small ghost girl making terrifying corn dolls. The audience is treated to glimpses of the creepy monsters that will later come to terrorise us, while the characters stay oblivious.

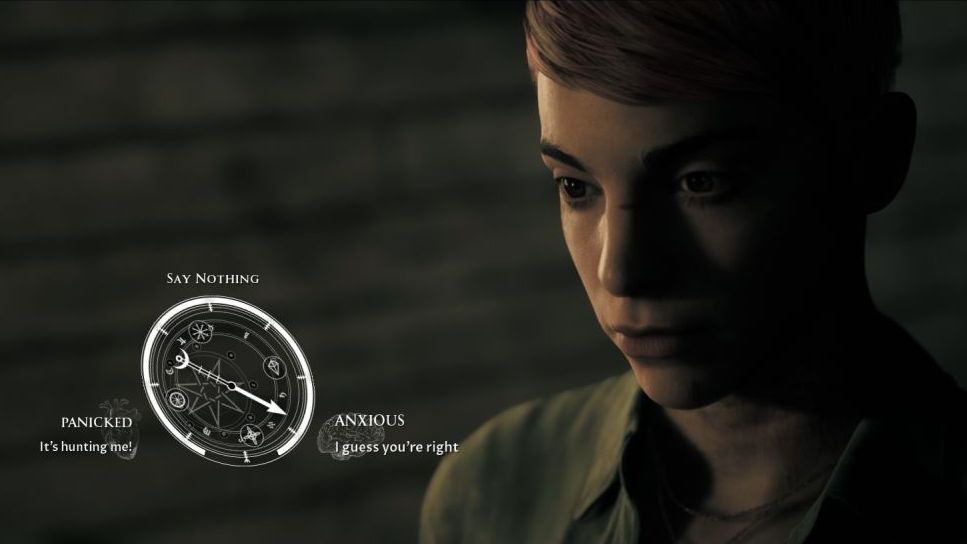

About half way through, though, it starts to feel like a producer crashed in and told the team that they were suddenly only allowed two hours more game. “But Bobert,” someone yells in alarm, “we have, like, at least four hours worth of stuff to fit in!”. And Bobert was like “tough shit” and smashed a flip chart over that dude’s head. Cuts in scenes become frequent and even start to feel slightly random. A key part of the game is the characters seeing the witch trials of the past by being physically dragged into it by jump scare ghosts, but for a couple of them they just tell each other they had one and it was totally scary. The central metaphors are kind of openly explained to you by the librarian-who-is-death character from the story-in-a-story framing conceit. Events start to take on a familiar rhythm, such that you know when to expect scares and stop reacting to them. It’s a shame, because the monsters themselves are decently scary, especially the way they’re introduced with lots of tight close ups of the particular ways their bodies are broken or otherwise horrific. It’s much more effective than big reveals of their whole look. One, a man who was crushed to death with the execution method known as crushing, is particularly unsettling. Alas, the quick time events, where you have to press the right button or hit the right body part as events drip into super slow-mo, often reveal too much of the scene for the monsters to stay scary. Little Hope is also rendered more funny than frightening because of how your choices affect the story and characters. At key points you’re given the option to save one character over another or, in dialogue, go with your head or your heart. It changes how the characters feel about each other, as well as leaning them towards different personality traits. Shaken all together, it tells the game which events and bits of dialogue to pull out of its deck of possibilities. The issue is that this often results in hilarious, broken-feeling bits.

Large chunks of dialogue have to work no matter what choices the player has taken, which results in all the characters sounding curiously anaemic and unbothered about the terrifying events they’re caught up in. They also don’t call each other out on obvious hypocrisy, like John telling Andrew he feels responsible for them all mere moments before hoofing it away from a monster without warning anyone else. But when the dialogue is more reactive, it often crashes into itself in quite spectacular fashion. In one (admittedly egregious example) I lost one character by failing a QTE, and Andrew said “I can’t believe she’s gone,” followed by a random scene transition, followed by Andrew then saying “I can’t believe she’s gone,” again. As Daniel, I was then given the option to respond with “I can’t believe she’s gone,” which obviously I did, and then cackled whilst shoving microwave popcorn into my mouth. It’s the best way to play Little Hope, really: with a friend, eating salty snacks, kind of not taking it seriously. It’s a step in the right direction for the Dark Pictures Anthology, but things Little Hope gets right are too often negated by the next thing it does.

The interweaving of the past and present is undercut by how obvious the weft is. The gradual revelation of the final plot twist in environmental storytelling is ruined by you having it telegraphed to you in dialogue hours before. The scares are defanged because you know exactly when they’re about to appear. Competent acting is stymied by weird editing. The central story about family and personal responsibility naturally has a wholly unfinished side bit about Catholic priests all being nonces. I think it might sort have been saying ’noncing is the real evil’. Which, in fairness, it is hard to argue against. I will co-sign that premise.

Look, it’s certainly very possible to spend an enjoyable evening playing Little Hope. But you have to calibrate your expectations towards B-movie, janky schlock-fest. If you go in wanting to have a spooky time that actually freaks your nut, I fear you’ll be disappointed.