In it, you play as Morris Lupton, erstwhile director of the Shelmerston museum, and ghost. Starting out dead does take a lot of the pressure off. Shelmerston is an unbelievably idyllic island community off the coast of England, in Channel Island territory, but it’s also on top of a dormant volcano. Except it turns out the volcano isn’t so dormant anymore, and you - accompanied by Morris’s also dead dog Sparky - must hunt out the ghosts of other Shelmerston residents to try and solve this impending problem.

To do this, you have to hunt through the world and find items that were important to each ghost when they were alive. This is where I Am Dead becomes a sort of spiritual game of Where’s Wally, or a 3D hidden object game. You see, ghosts like wot Morris is have the ability to ‘slice’ into objects, looking through their various layers to see the insides, which you can do with either keyboard or mouse very smoothly. So, if you look into a fridge, you might see all the vegetables in the bottom drawer. And then you can go and look inside the vegetables, and in the heart of a lettuce you might find a little worm, monching away.

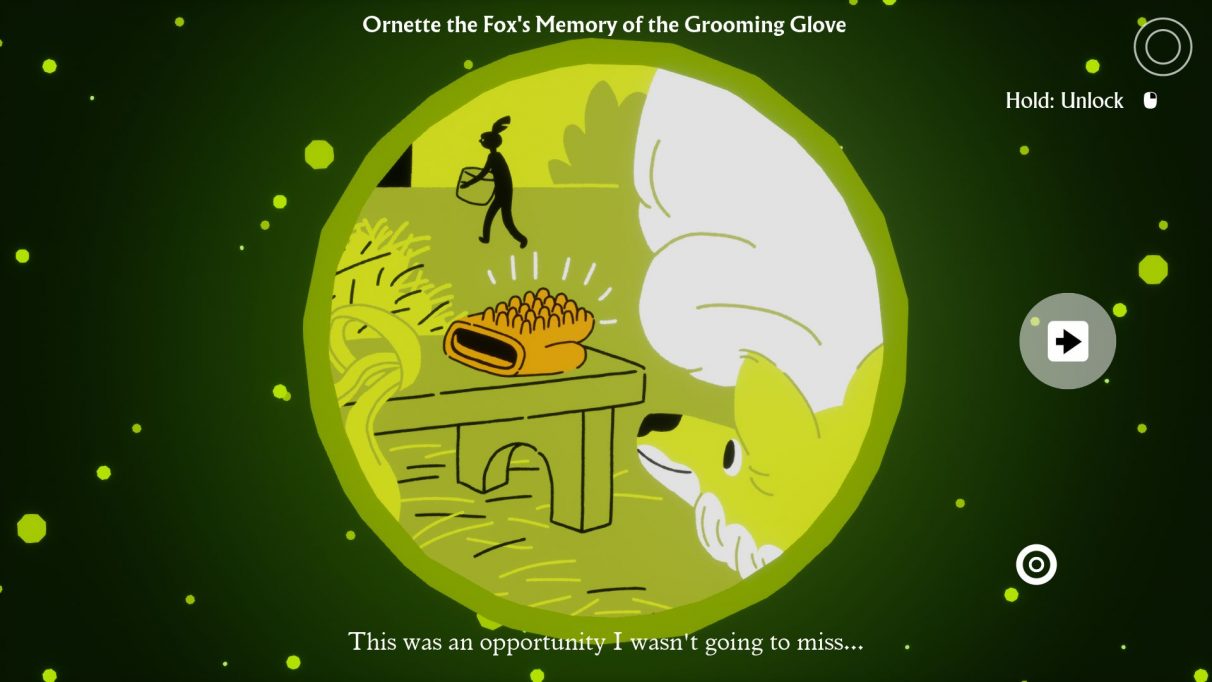

Not that a worm is one of the items you’re likely going to be tasked with finding. They’re more significant than that, and first you must get an idea of what they are by slicing into the memories of someone who knew the spirit when they were alive. These folks are indicated by little thought bubbles popping up from their head. By lining up the images of their memories correctly, you get a nice little story - like a fox remembering the time they stole a very important glove. Then, using the same logic that places a worm in a lettuce, you think, “Where would a fox put a glove?” The fox is next to a bush full of gloves, this is true, but the special glove doesn’t appear to be one of them. So where else would a fox put things… And once you find the six or so items you need, Sparky can sniff down the spirit and you have a chat about Shelmerston.

Each ghost is in a different location - the harbour, a campsite, a lighthouse that’s been turned into a yoga retreat, for example - and each of these locations hold several surprises. They’re not really related to the things you have to find, but they’re there for the inquisitive slicer nonetheless - and many of them revealing a secret or a truth about the people of Shelmerston. The sailors are all smugglers, the toilet might have a lobster in it, and the lighthouse is full of mismatched pairs of Crocs. It’s all put together with gentle, but good, humour. I liked looking in food to see what was lurking inside piecrusts, and how examining items at the museum revealed curious things about the vegetable growing competition. At one point, you find yourself looking for a small, dark, round object in ’the place where the rabbits poo’.

You’re encouraged to explore and experiment with slicing by looking for Grenkins, little spirits that hide everywhere on the island and are revealed only when you slice a certain object into a certain cross section, or with challenges set by a strange giraffe-like creature who sends you on treasure hunts for more hidden items, for some dark and unexplained purpose of his own. Each of these areas gets a little bigger, and a litter more complicated to navigate, with more things to slice into. And in these later stages it feels like there are fewer surprises to find, or perhaps they just get lost amongst all the lettuces that don’t have worms in this time. But you still feel compelled to turn over every lettuce, as it were, like an increasingly paranoid Mr McGregor worrying that he missed the signs of even one bastard rabbit. My fear of missing out put back some of the stress that being dead had initially removed.

Still, Shelmerston is an honestly charming place to visit, while also being a bit strange. The art is bright, round and cosy, but its plants and foods still make it look strange and exotic - a bit like the excellent (and also very chill) Mutazione. Some of the inhabitants are big bipedal fishfolk with curiously blank, smiley faces, for example, and there are tourists who are just really big birds. Some animals have either both eyes on one side of their head, or one big one on the front, and this is apparently unremarkable. Which is, itself, charming. Likewise, as you listen to the stories of the locals (all voice-acted very well, to various levels of eccentricity) and gradually uncover the history of Shelmerston, you realise how much everyone who lives there really loves the place. The love is deep in their very bones, and it makes you love it too. For the six to eight hours it took me to reach the end credits, it even fooled me into thinking I liked my own hometown, which is not true. I hate where I’m from. That’s okay though, because I choose to be from Shelmerston now.