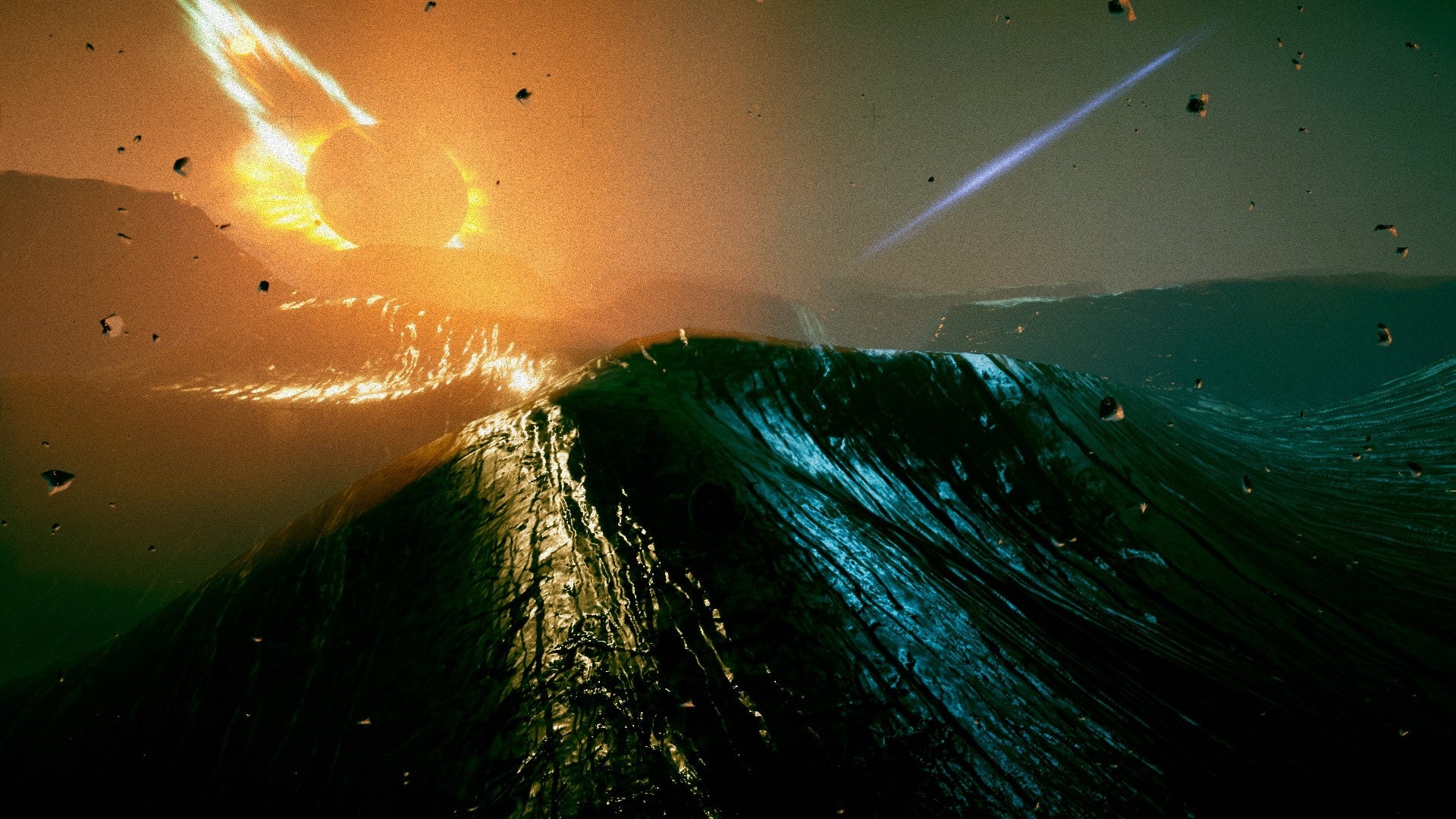

I don’t think it’s reductive to describe Exo One as Christopher Nolan’s Tiny Wings. Nolan would appreciate this planet-hopping journey across space and time for its vast scale. Each planet it takes you to is huge, and the best of them have an equally epic high concept. In early planets, this tends to mean they are meteorologically banjaxed in some way: I skimmed across water worlds as they were pummelled by meteors, tumbled like a marble down erupting volcanic mountains, and hurled myself through lightning storms. Mobile classic Tiny Wings, meanwhile, is invoked by your spacecraft and its unusual method of propulsion. It has no engine, but instead manipulates gravity to alternately plunge downhill or float through the air. Using these abilities in tandem turns each world’s surface into a ski resort, and hitting the next Cairngorm-sized ramp just right feels as if it slingshots you the distance from Aberdeen to Dundee. This scale is both the game’s appeal and, I think, its downfall. Whatever the nature of the planet, your objective mostly remains the same: reach the distant white light shooting into the sky which will fire you like a cannonball towards the next planet. My initial attempts to navigate in Exo One were clumsy. I’d mis-time my drops and miss the slope I was aiming for, or stop plunging too late and roll back downhill towards the way I came. It feels lousy to constantly lose momentum and to rebuild it from scratch. It is possible to make progress just by pushing forwards and rolling your ballform steadily across the ground, but doing so feels like the equivalent of taking your skis off and opting to walk. Then, after 30 minutes or so of awkward progress, success! I found the rhythm of the terrain, began to fall with style, and was soon covering large distances at great speeds. It was exhilarating, at first, as I skated over mountain ranges and flung my ship so high it broke through the clouds. Yet my quick glide up the game’s learning curve also stripped Exo One of any friction, in every sense. While pootling around on the floor feels awkward and slow, gliding through the air mostly feels like nothing at all. There’s no sense of speed once you’re up high. Exo One wisely forces you back down - plummeting recharges your glide - but once this move becomes trivial to perform, doing it over and over again reveals the difference between planets to mostly be cosmetic. Whether water, lava or snow, mountain ranges or floating islands in the sky, I did the same thing over and over in Exo One. I’d rush downhill to build up speed and charge my ship; switch to gliding on the upslope until that charge ran out; and then back on the downhill to start the process over. And again. And again. Then head to a new planet and do it some more. Tiny Wings was a score attack game designed around brief bursts of play. Exo One is a single story experience and it needs players to be able to make continual progress. Stripped of most challenge, that makes tourism its core appeal - a galactic Abzû or hard science Rez Infinite, games I love - but after a few minutes on each new world even Exo One’s visual impact wears off. I felt, at times, like a Tribes player who’d gone AWOL in the procedural infinity beyond the real level’s borders. There are a handful of attempts to reintroduce challenge. There are optional collectibles which extend your glide’s maximum charge, which is fine. In a couple of worlds you’re encouraged to fly through smaller tunnels and flumes, but it never feels good to wrangle your momentum and wide turning circle in tight spaces. A later planet hobbles some of your ship’s abilities outright, but it makes overcoming the undulating terrain more cumbersome rather than more interesting. On the game’s most geographically ambitious levels, Exo One’s camera lets it down. It likes to get so close that your ship goes into spinning confusion over which way to face, and in moments where the distances are so vast that there’s no scenery to use as a frame of reference, it’s difficult to know how to bring your craft back under control. At this point, Exo One’s last hope in maintaining momentum is the story tying your journey together. Told via snippets of dialogue and static images which occasionally flicker onscreen, it successfully amplifies the feeling of insignificance and alienation communicated by the game’s cosmic scale - but its either too simple or too vague to be compelling. Beyond its success as a mood piece, it’s tempting to recommend Exo One solely for its scenery. As a machine for generating desktop wallpapers or screensavers, it’s first rate. Some of you, I feel, will love it for this alone. But as I said up top, maybe I just don’t like sci-fi vistas as much as I thought I did. Long before Exo One’s short three hours reached their conclusion, I just wanted it to be Exo Done.