So Deathtrap Dungeon, yeah? It’s that. Only it’s a game rather than a fish. And rather than providing a haunting glimpse down through the yggdrasilian roots of tetrapod biology, it’s a showcase of how simultaneously charming and rubbish 1980s trad fantasy was.

It’s an FMV game, a format that’s a bit of a living fossil itself, despite something of a recent comeback, and it’s based on the legendary Fighting Fantasy gamebook of the same name, authored by Monsterpreneur and Games Workshop co-founder Ian Livingstone. Well, I say it’s based on it, when what I really mean is that it is it. It’s Deathtrap Dungeon, read out to you word for word by the eminently likeable Eddie Marsan, with branch points marked by clickable on-screen options. It even features DD’s original illustrations by the unmistakable Iain McCaig, presented from time to time as sepia-tinted vignettes.

If you’re not familiar with Fighting Fantasy gamebooks, they were the pinnacle of the British take on the “choose your own adventure” concept, featuring branching stories that took the reader through robustly uninventive fantasy settings. They were peppered throughout with sudden, random deaths, and fights with monsters that involved rolling dice, continuously rubbing out hitpoint totals, and quietly ignoring fatal consequences with a vague sense of guilt. In Deathtrap, you’re a generic adventurer, seeking to enter the titular labyrinth, which has been built by some wanker called Baron Sukumvit as a sort of underwhelming gameshow/tourist attraction under the village of Fang. And this is a digression, but I really don’t get why crowds turn up every year to go absolutely mental watching new challengers enter the Baron’s dungeon. I’d understand if they got to watch people being mangled by giant scorpions or turned to stone by gorgons and that, but they don’t. They’re just watching people walk into a hole?

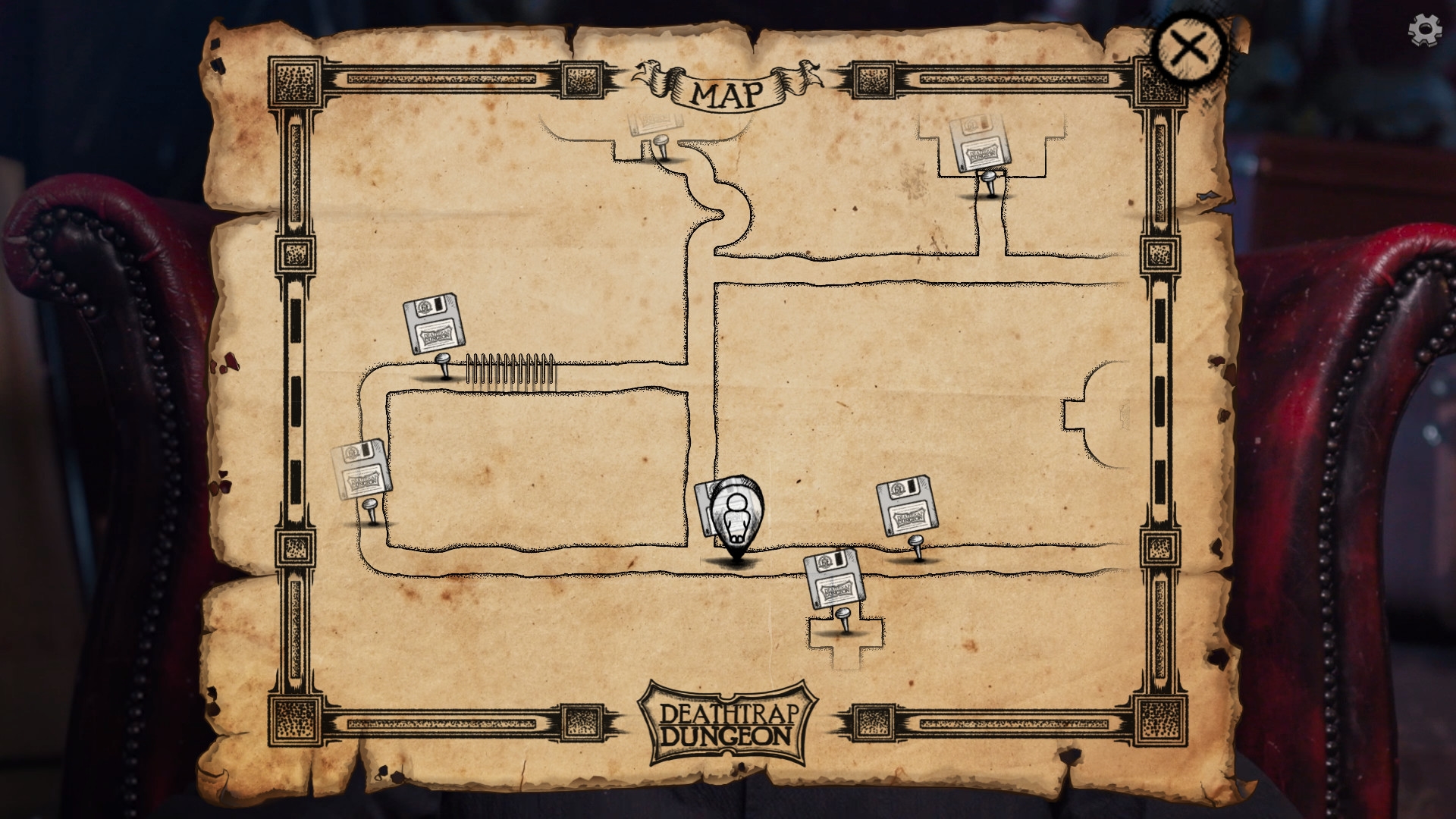

Anyway. Making an FMV version of DD was, I’ll concede, a genius idea for an adaptation. Because the two biggest failings of Fighting Fantasy were the sheer administrative burden involved in tracking stats on paper as you played through, and the books’ complete powerlessness in stopping you from cheating. Deathtrap Dungeon (or to give it its full title, Deathtrap Dungeon: The Interactive Video Adventure, which manages to feel dated itself in using the words “interactive video”, but at least differentiates it from 1998’s middling action-adventure adaptation of the same book), is a much more empowered GM. It holds you to the rules of the gamebook exactingly, keeping track of all the numbers for you, and although it does save your game regularly, if you get dannied by a goblin or whatever, you’re sent back to the last checkpoint.

And there’s the problem. Because when you have to actually stick to the rules, Deathtrap Dungeon is a bit rubbish. Instant death moments can occur arbitrarily at any time, with barely a narrative clue to foreshadow them, and the combat system is guff. In their one concession to modernisation, developers Branching Narrative have included an optional, streamlined version that mercifully ends each interminable stranglefest after three rounds of dice rolls, but even then it’s a clumsy, unenjoyable system. And because it would be weird to just have Eddie stare silently at you through fights, he has to constantly narrate the outcome of each blow, repeating “you sweep the creature’s legs from under it” and the like over and over, as if he’s got a peculiarly specific set of Tourette’s tics.

Then there’s the overall win condition of the dungeon, which isn’t just to survive, but to… ah, well, I won’t say it because I suppose it’s a spoiler, but it’s a win condition you won’t know about until you fail to achieve it, unless you happen to have one specific conversation with an NPC. If you want to manage it, there’s only one correct sequence of decisions through the entire game, and since many of the steps involve taking options that make the most obtuse point and click “puzzles” seem intuitive, the only way to arrive at it is through trial and error, or by looking up a walkthrough. It made me think of John Walker’s recent piece on the King’s Quest games, and how the expectation that adventure games should be in any way fair seems to be a surprisingly modern idea.

But all this criticism is irrelevant, really. Because if we’re being honest, I’d be surprised if anyone came to Deathtrap Dungeon: The Interactive Learning CD-ROM looking for a fantastic adventure game, or even a functional RPG. Just as you wouldn’t seek out a coelacanth if you wanted to see an example of a real top-of-the-line, high performance sports fish. It’s a slice of intense nostalgia for those who played the gamebook in 1984, and a window into the past for younger fantasy fans, who will have grown up on a diet of games influenced in some way by the explosion of barbarians, giant insects and orcs that took place in the 70s and 80s.

I’ve got a foot in both camps mentioned above. Deathtrap Dungeon itself was published just five months before I was, but as a child of the 90s, I knew the formula. I spent hours flicking through gamebooks of various imprints, with no regard to the rule of law, as I tried to block out the sound of my nan screaming her way through the long, hideous aftermath of a stroke. As such, Deathtrap Dungeon: The Online Edutainment Experience was freighted with wistful memories for me, but it was also a chance to think critically about how fantasy has changed in the last three decades. I’ve gotten so used to modern genre fiction’s constant attempts to innovate cliché, that to experience so much unrefined generica actually felt refreshing. And weird. To encounter a barbarian who really was just a hulking, taciturn man with a sword was disconcerting when I’d forgotten that such things ever existed outside of deliberate parody. It was a relief as strange and pure as eating a half-rate fryup on a 50p plate, after years of bourbon-infused bacon and sourdough served on shovels and bits of masonry.

And of course there’s Marsan, who’s just lovely. Here is a man who is the very definition of a supporting actor, and I guarantee you he’s appeared in about twenty movies you’ve seen, doing solid work with characters usually just above the threshold of being named in the script. He was the science man in 2019’s sublime Statham Containment Vessel Hobbs & Shaw, for example, and the grim headmaster in Deadpool 2. He always does a good job. And he does a great job here. Marsan is a faintly awkward presence at first, sitting with the shy smile of a trainee vicar, in a red leather armchair so big he looks like he might get lost in it. But he’s so wholeheartedly, enthusiastically professional about every damned word of the script, that it’s impossible not to buy into it.

And he’s a great reader! He does weird voices for the NPCs and everything, making the most of even the text’s mediocre stretches, and injects real passion into his attempts to infuse situations with danger, mystery and tension. Sometimes, admittedly, the relish with which he intoned “your adventure ends here” through a dark smirk made me feel a bit like he was about to suggest we have sex, but on the whole, it was miraculously cringe-free. It’s Knightmare by way of an ASMR video, and it works way better than it should. There’s a free demo, playable in your browser on the game’s website, if you want a look.

And right now, with what feels like 80% of my friends running some kind of lockdown RPG campaign, it felt really good to have my own personal GM for a bit. It was face to face contact, and personal attention. And as illusory as it was, at a time like this you’ll take what you can get. It was like the social equivalent of prison wine. More than that, though, it felt like having a guide to something fascinating. Like at one of those ’living history’ museums, where volunteer enthusiasts LARP as tudors or romans or whatever, and talk to you in character about the olden days while you look at an old engine or some geese. And there you go. Rather than being a game, Deathtrap Dungeon is a lovingly curated museum, and I think a tenner is a more than reasonable price for entry.